Watch Carole's Commentary On Watch Night Below...Dear Family, Valuable Friends, Clients, and Colleagues:

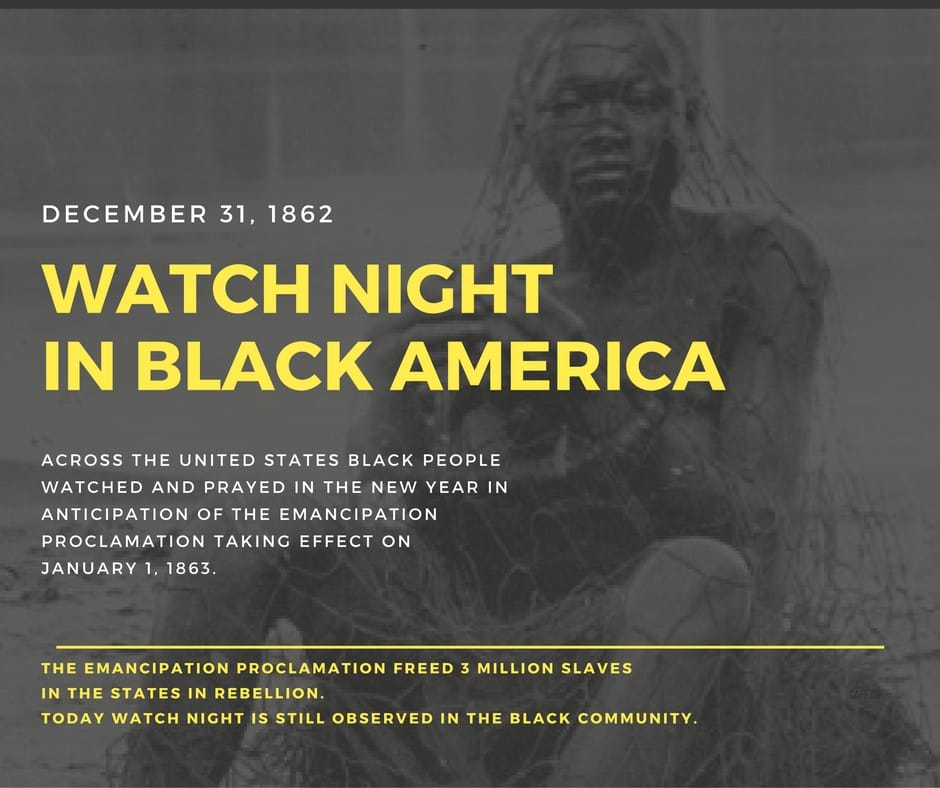

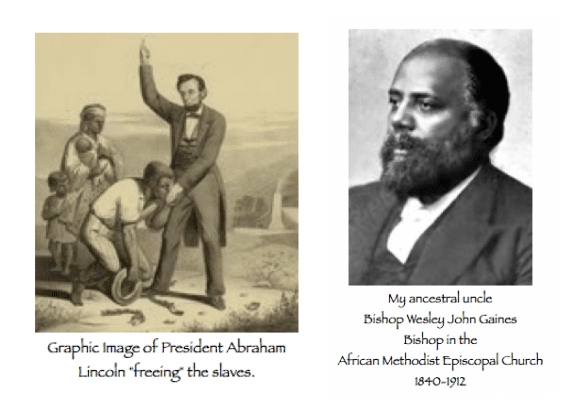

From my home to yours, I wish you rich blessings into the New Year. Here is a special article I created about the history of Watch Night Service in the African American community. The tradition predates the importance of the famous 1862 Watch Night Services and originated with the Moravians in Germany many years earlier. The first Methodist church in America to celebrate Watch Night in the 1700s was St. George United Methodist Church in Philadelphia, the home church of Bishop Richard Allen, co-founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. However, it has become particularly important in the Black Church, with its evolution in the early to mid-1800s. The word evolved from “Freedom’s Eve” to “Watch Night” as the freed and enslaved blacks “watched” the clock strike 12 midnight, turning the course of the Civil War and freeing 3 million slaves in the states of the rebellion. Wishing You The Best in 2017 ! Carole Copeland Thomas, MBA CDMP, CITM --------------------------- The History Of Watch Night Services In The Black Church by Carole Copeland Thomas With the festivities of Christmas, Hanukkah, and Kwanzaa now on full display, there is still time to reflect on the ritual of my ancestors and many other African Americans, whose forefathers sat around campfires and wood stoves in the twilight of December 31, 1862. There they sang spirituals acapella, prayed, and thanked the Good Lord for what was about to happen the next day. In the North Abolitionists were jubilant that the “peculiar institution” was finally about to get dismantled one plantation at a time. The booklet, Walking Tours of Civil War Boston sites this about this historic event: “On January 1, 1863, large anti-slavery crowds gathered at Boston’s Music Hall and Tremont Temple to await word that President Abraham Lincoln had issued the much-anticipated Emancipation Proclamation (EP). Those present at the Music Hall included Uncle Tom’s Cabin author Harriet Beecher Stowe, poets Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and John Greenleaf Whittier and essayist, poet and physician Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. Also present was Ralph Waldo Emerson, who composed his Boston Hymn to mark the occasion.” Now… Let’s Look Back...154 Years Ago Tonight... It was on January 1, 1863 amidst the cannon fire, gun shots, and burnings at the height of the Civil War that President Abraham Lincoln sealed his own fate and signed the Emancipation Proclamation. It begins with the following decree: Whereas on the 22nd day of September, A.D. 1862, a proclamation was issued by the President of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, towit: "That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.” That the Executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State, or the people thereof, shall on that day be, in good faith, represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such State shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State, and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States." CAROLE' S TRANSLATION: Effective January 1, 1863 all slaves in the states in rebellion against the Union are free. Technically that is all that President Lincoln could do at the time. He used his wartime powers as Commander in Chief to liberate the "property" of the states in rebellion of the Union. The act did not free the slaves of the Union or border states (Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, or West Virginia) or any southern state under Union control (like parts of Virginia). It would take the 13th Amendment (that freed all slaves in 1865), the Union Army winning the Civil War (April 9, 1865), and the assassination of President Lincoln (shot on April 14th and died on April 15, 1865) for all of the slaves to be freed. That included the liberation of the slaves in rebellious Texas on June 19, 1865 (Juneteenth Day) and finally the ratification of the 13th Amendment on December 18, 1865, giving all black people freedom and permanently abolishing slavery in the US. So in 1862 on the eve of this great era, the slaves "watched", prayed, and waited. My ancestors, including Bishop Wesley John Gaines of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) (a slave in Georgia freed by the EP) and the other three million slaves prayed for divine guidance and an empowered Abraham Lincoln to do the right thing. It is as important today as the tradition of black people eating black eyed peas on New Year's Day for good luck. Following the Emancipation Proclamation slaves were freed in stages, based on where they lived, the willingness of the plantation owner to release them and when Union troops began to control their area. Black educator and community activist Booker T. Washington as a boy of 9 in Virginia, remembered the day in early 1865: “As the great day drew nearer, there was more singing in the slave quarters than usual. It was bolder, had more ring, and lasted later into the night. Most of the verses of the plantation songs had some reference to freedom. ... Some man who seemed to be a stranger (a United States officer, I presume) made a little speech and then read a rather long paper—the Emancipation Proclamation, I think. After the reading we were told that we were all free, and could go when and where we pleased. My mother, who was standing by my side, leaned over and kissed her children, while tears of joy ran down her cheeks. She explained to us what it all meant, that this was the day for which she had been so long praying, but fearing that she would never live to see.” The longest holdouts were the slaves in Texas, who were not freed until June 19, 1865, two months after the Civil War ended. That day is not celebrated as Juneteenth Day around the United States. That is the history of Watch Night in the African American culture. May you and your family enjoy a spirit filled New Year throughout 2017. Thank you for ALL of your support you have given to me and my business throughout 2016. -Carole

1 Comment

By Carole Copeland Thomas, MBA, CDMP The Civil War ended in 1865, and now more than 150 years later the battle flag of the Southern states is still at the crossroads in South Carolina, Mississippi, Georgia and elsewhere. From license plates to T-shirts to flags, the "stars and bars" remains a hateful symbol of slavery to the Black community.

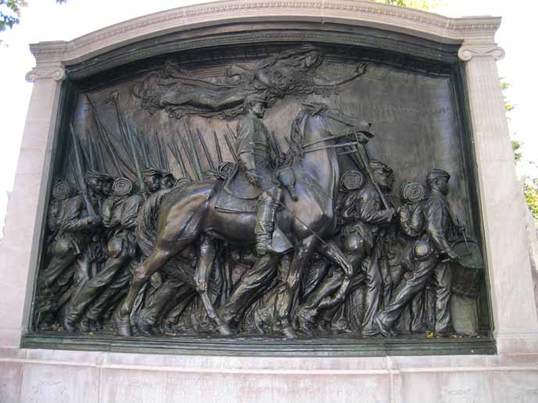

With the execution of nine innocent African Americans merely attending Bible study at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina on June 17, 2015, the killer was a 21 year old White supremacist who cherished the Confederate flag. With racial hatred and gun violence robbing this country of true progress, it’s time to take down the Confederate Flag and park it in a museum where it belongs. ===================== For More On The Various Versions of the Confederate Flag Visit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flags_of_the_Confederate_States_of_America http://confederatemuseum.com/collections/flags http://www.confederatemuseumcharlestonsc.com/about.html Perhaps you saw the award winning movie, “Glory” when it debuted in 1989 or later on DVD or On Demand. Starring Denzel Washington, Matthew Broderick and Morgan Freeman, the film celebrates the heroic efforts of one of the first all Black regiments during the Civil War. The Massachusetts 54th Regiment victories came at a heavy price, including the death of their White commander, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw who died during the 1863 attack of Fort Wagner, South Carolina. The men who fought and died helped to ultimately win the Civil War, and their struggles, setbacks and amazing levels of courage should never be forgotten.

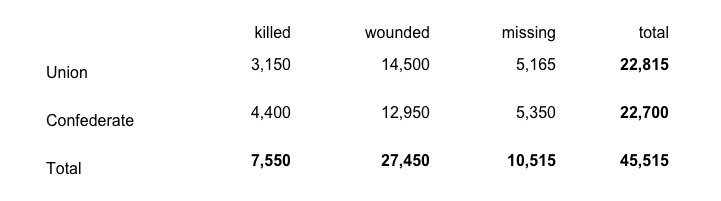

I often pass the monument that was erected on Beacon Street in Boston across from the Massachusetts State House. It pays tribute to the men of the 54th who fought, lived and died so that ultimately all men and women could be free in America. As we close out our tribute to Memorial Day, we pay tribute those who sacrificed their lives in all wars fought by Americans. We pay a special tribute to the Civil War era men of the Massachusetts 54th Regiment. Read More About Them Below… -Carole Copeland Thomas ======================= The Massachusetts 54th Regiment The Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Regiment Memorial, located across Beacon Street from the State House, serves as a reminder of the heavy cost paid by individuals and families during the Civil War. In particular, it serves as a memorial to the group of men who were among the first African Americans to fight in that war. Although African Americans served in both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, northern racist sentiments kept African Americans from taking up arms for the United States in the early years of the Civil War. However, a clause in Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation made possible the organization of African American volunteer regiments. The first documented African American regiment formed in the north was the Massachusetts 54th Volunteer Infantry, instituted under Governor John Andrew in 1863. African American men came to enlist from every region of the north, and from as far away as the Caribbean. Robert Gould Shaw was the man Andrew chose to lead this regiment. Robert G. Shaw was the only son of Francis George and Sarah Blake (née Sturgis) Shaw. The Shaws were a wealthy and well connected New York and Boston family. They were also radical abolitionists and Unitarians. Robert did not blindly follow his parents ideological and religious beliefs, but all recognized the importance and responsibility involved in leading the Massachusetts 54th Regiment. The Massachusetts 54th Regiment became famous and solidified their place in history following the attack on Fort Wagner, South Carolina on July 18, 1863. At least 74 enlisted men and 3 officers were killed in that battle, and scores more were wounded. Colonel Shaw was one of those killed. Sergeant William H. Carney, who was severely injured in the battle, saved the regiment’s flag from being captured. He was the first African American to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. The 54th Regiment also fought in an engagement on James Island, the Battle of Olustee, and at Honey Hill, South Carolina before their return to Boston in September 1865. Only 598 of the original 1,007 men who enlisted were there to take part in the final ceremonies on the Boston Common. In the last two years of the war, it is estimated that over 180,000 African Americans served in the Union forces and were instrumental to the Union’s victory. Augustus Saint-Gaudens took nearly fourteen years to complete this high-relief bronze monument, which celebrates the valor and sacrifices of the Massachusetts 54th. Saint-Gaudens was one of the premier artists of his day. He grew up in New York and Boston, but received formal training at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts Paris. In New York, forty men were hired to serve as models for the soldiers’ faces. Colonel Shaw is shown on horseback and three rows of infantry men march behind. This scene depicts the 54th Regiment marching down Beacon Street on May 28, 1863 as they left Boston to head south. The monument was paid for by private donations and was unveiled in a ceremony on May 31, 1897. Sources: National Park Service Wikipedia One of the major battles and turning points of the Civi War was the Battle of Gettysburg fought over three days from July 1-3 1863. It marked the turning point in the War Between The States, giving the Union Army the winning advantage in the months and years that would remain. Bloody and hard fought, both sides extracted terrible losses in the dead, wounded and missing. It has gone down in history as one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War and has been associated with one of the reasons why Memorial Day was founded. In November 19, 1863 at the Soldiers National Cemetery near the battlefield two great speeches were made in honor of the dead and wounded. One was the 1 hour 57 minute speech by political statesman Edward Everett of Massachusetts. He was followed by the speech that lasted less than three minutes…made by President Abraham Lincoln. The President’s speech was so short that the photographers didn’t have time to set up their cameras to take pictures of him delivering his message. It didn’t matter. It was so profound that it has gone down to become one of the greatest speeches in American history, recited by politicians and school children alike, including my daughter, Lorna, when she was in middle school. Below are the highlights of The Battle of Gettysburg. As you continue with your picnics, barbecues and visions of the upcoming summer season, think on these words and why Memorial Day will forever honor those who died in military service in America. -Carole Copeland Thomas, MBA, CDMP ================== The Battle of Gettysburg Fought over the first three days of July 1863, the Battle of Gettysburg was one of the most crucial battles of the Civil War. The fate of the nation literally hung in the balance that summer of 1863 when General Robert E. Lee, commanding the "Army of Northern Virginia", led his army north into Maryland and Pennsylvania, bringing the war directly into northern territory. The Union "Army of the Potomac", commanded by Major General George Gordon Meade, met the Confederate invasion near the Pennsylvania crossroads town of Gettysburg,and what began as a chance encounter quickly turned into a desperate, ferocious battle. Despite initial Confederate successes, the battle turned against Lee on July 3rd, and with few options remaining, he ordered his army to return to Virginia. The Union victory at the Battle of Gettysburg, sometimes referred to as the "High Water Mark of the Rebellion" resulted not only in Lee's retreat to Virginia, but an end to the hopes of the Confederate States of America for independence. The battle involved the largest number of casualties of the entire war and is often described as the war's turning point.Union Maj. Gen. George Meade's Army of the Potomac defeated attacks by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, ending Lee's attempt to invade the North. The battle brought devastation to the residents of Gettysburg. Every farm field or garden was a graveyard. Churches, public buildings and even private homes were hospitals, filled with wounded soldiers. The Union medical staff that remained were strained to treat so many wounded scattered about the county. To meet the demand, Camp Letterman General Hospital was established east of Gettysburg where all of the wounded were eventually taken to before transport to permanent hospitals in Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington. Union surgeons worked with members of the U.S Sanitary Commission and Christian Commission to treat and care for the over 20,000 injured Union and Confederate soldiers that passed through the hospital's wards, housed under large tents. By January 1864, the last patients were gone as were the surgeons, guards, nurses, tents and cookhouses. Only a temporary cemetery on the hillside remained as a testament to the courageous battle to save lives that took place at Camp Letterman. How many casualties were there in the Battle of Gettysburg? How many people died at Gettysburg? Gettysburg was the bloodiest battle of the Civil War. Until Gettysburg that title had gone to the Battle of Chancellorsville, fought just two months before. And although later battles such as The Wilderness and Spotsylvania would surpass Chancellorsville, Gettysburg would remain the costliest Civil War battle. It is estimated that there were at least 45,000 and possibly as many as 51,000 casualties in the two armies at Gettysburg. Note: the term “casualties” means not just people who were killed, but also includes men who were wounded (many of whom may have died of their wounds later), soldiers who were captured, and even men who ran away. It’s impossible to calculate an exact number because of missing or incomplete records. This estimate is one of the more conservative and probably significantly understates Confederate missing and wounded: Were any civilians killed in the Battle of Gettysburg?

Hundreds of civilians sheltered in their homes as the fighting raged around them and one, John Burns, joined the fight and was wounded. But only one civilian, Jennie Wade, was killed during the Battle of Gettysburg. She was struck by a stray shot while indoors in a house on the south side of town caring for a sick relative. Honoring The Dead After The Fight Had Ended Prominent Gettysburg residents became concerned with the poor condition of soldiers' graves scattered over the battlefield and at hospital sites, and pleaded with Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin for state support to purchase a portion of the battlefield to be set aside as a final resting place for the defenders of the Union cause. Gettysburg lawyer David Wills was appointed the state agent to coordinate the establishment of the new "Soldiers' National Cemetery," which was designed by noted landscape architect William Saunders. Removal of the Union dead to the cemetery began in the fall of 1863, but would not be completed until long after the cemetery grounds were dedicated on November 19, 1863. The dedication ceremony featured orator Edward Everett and included solemn prayers, songs, dirges to honor the men who died at Gettysburg. Yet, it was President Abraham Lincoln who provided the most notable words in his two-minute long address, eulogizing the Union soldiers buried at Gettysburg and reminding those in attendance of their sacrifice for the Union cause, that they should renew their devotion "to the cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion..” Sources: The US National Park Service Wikipedia Battle of Gettysburg Facts: http://gettysburg.stonesentinels.com/battle-of-gettysburg-facts Memorial Day, originally called Decoration Day, is a day of remembrance for those who died in service to their country. The holiday was officially proclaimed in 1868 to honor Union and Confederate soldiers and was expanded after World War I to honor those who died in all wars. Today, Memorial Day honors over one million men and women who have died in military service since the Civil War.

By the 20th century, competing Union and Confederate holiday traditions, celebrated on different days, had merged, and Memorial Day eventually extended to honor all Americans who died while in the military service. It typically marks the start of the summer vacation season, while Labor Day marks its end. Memorial Day is not to be confused with Veterans Day; Memorial Day is a day of remembering the men and women who died while serving, while Veterans Day celebrates the service of all U.S. military veterans. My Memories: Town Gatherings, Celebrations, Parades and The Gettysburg Address Remembering the Gettysburg Address is frequently a symbolic part of Memorial Day traditions. Years ago my daughter, Lorna, recited the Gettysburg Address during a town wide program, while her sister, Michelle, and brother, Mikey, played the flute and saxophone with the school band. I believe the program took place in the town cemetery to honor our war dead. From Decoration Day To Memorial Day What is “decorated?” Gravestones and cemetery plots of deceased soldiers who died in military service. Many people visit cemeteries and memorials, particularly to honor those who have died in military service. Many volunteers place an American flag on each grave in national cemeteries. The preferred name for the holiday gradually changed from "Decoration Day" to "Memorial Day", which was first used in 1882. It did not become more common until after World War II, and was not declared the official name by Federal law until 1967. On June 28, 1968, the Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act, which moved four holidays, including Memorial Day, from their traditional dates to a specified Monday in order to create a convenient three-day weekend. The change moved Memorial Day from its traditional May 30 date to the last Monday in May. The law took effect at the federal level in 1971. After some initial confusion and unwillingness to comply, all 50 states adopted Congress' change of date within a few years. Sources: www.census.gov and wikipedia.org |

* * * * * * * *Archives

July 2024

|

©2024 All Rights Reserved Carole Copeland Thomas • (508) 947-5755 • [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed